So, the manuscripts at Cambridge University Library are amazing.

Once again, it was a serendipitous experience: a novice American "primary" teacher wanders into the manuscripts room at the University library and points to a page of primary materials that are available. The manuscripts helper looks at her quizzically and asks what specifically she wants. She shrugs her shoulders and says, "Anything! This is just too exciting!"

He then pulls indices of the records from World War II, but in her ignorance, she thinks he is actually pulling the sources. Again, her joy is met with a strange look as he prompts her to fill out a "fetching card" before they "stop fetching" at five p.m. She nods affirmatively, and finally understands what she is looking at is not the actual sources, but an index of the sources available.

After three tries of asking for a source to be fetched (she can't quite discern how the sources are housed at the different institutions; evidently, Christ's Church resources CANNOT be found at the University Library's sources), she, in a panic to meet the five p.m. deadline, hastily asks for Viscount Templewood's correspondence about "Human Rights from 1944-1947."

When the speeches and letters finally arrive, she weeps over the pure magic of it all; whomever this Viscount Templewood (real name, Sir Samuel Hoare) was, she is looking at his speeches with his handwritten notes on it. The University LIbrary's staff smiles patiently at her, but does not quite understand the power that these seventy year old documents have over her.

... and it is with that stage that has been set that I discovered Templewood:

"The Law of Humanity (a minimum standard for Europe): 'The fact that Germany, a country once regarded as a civilized state, abolished the most elementary human rights, is an extremely serious danger-signal. Where is the guarantee that a similar development might not emerge in other countries?... “Mankind has to be protected from a repetition of the German example. It should be recognized that beastality does not confine itself to the land where it was born and attained mastery. The evil proved to be more dynamic and more contagious than the good. This is the reason why a country where the law of humanity has been abolished becomes a danger to all other countries...Among the measures of a national character the incorporation of the Law of Humanity into the different state constitutions as a completely separate part could gradually gain a decisive role in the protection of human rights in any political development. This Law of Humanity should become the minimum standard for Europe...'"

Now, I have no real context of where these speeches were given, and I now only know a very little about Viscount Templewood, but certainly, anyone arguing at such a high level (he spoke at the Royal Institute for International Affairs on Tuesday, November 20th, 1945) for the respect of the individual should be someone who is included in the dialogue about the Upstander.

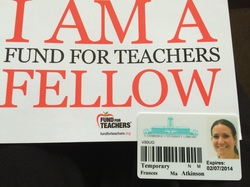

It is these magical moments that I treasure in my novice research experience. I had never heard of Templewood, and had I not become a temporary member of the University Library, I might not ever have found him.

My time in Cambridge has come to an end, sadly, but I am traveling to London and cannot wait to research there.

I might even get a temporary British Library ID!!

Once again, it was a serendipitous experience: a novice American "primary" teacher wanders into the manuscripts room at the University library and points to a page of primary materials that are available. The manuscripts helper looks at her quizzically and asks what specifically she wants. She shrugs her shoulders and says, "Anything! This is just too exciting!"

He then pulls indices of the records from World War II, but in her ignorance, she thinks he is actually pulling the sources. Again, her joy is met with a strange look as he prompts her to fill out a "fetching card" before they "stop fetching" at five p.m. She nods affirmatively, and finally understands what she is looking at is not the actual sources, but an index of the sources available.

After three tries of asking for a source to be fetched (she can't quite discern how the sources are housed at the different institutions; evidently, Christ's Church resources CANNOT be found at the University Library's sources), she, in a panic to meet the five p.m. deadline, hastily asks for Viscount Templewood's correspondence about "Human Rights from 1944-1947."

When the speeches and letters finally arrive, she weeps over the pure magic of it all; whomever this Viscount Templewood (real name, Sir Samuel Hoare) was, she is looking at his speeches with his handwritten notes on it. The University LIbrary's staff smiles patiently at her, but does not quite understand the power that these seventy year old documents have over her.

... and it is with that stage that has been set that I discovered Templewood:

"The Law of Humanity (a minimum standard for Europe): 'The fact that Germany, a country once regarded as a civilized state, abolished the most elementary human rights, is an extremely serious danger-signal. Where is the guarantee that a similar development might not emerge in other countries?... “Mankind has to be protected from a repetition of the German example. It should be recognized that beastality does not confine itself to the land where it was born and attained mastery. The evil proved to be more dynamic and more contagious than the good. This is the reason why a country where the law of humanity has been abolished becomes a danger to all other countries...Among the measures of a national character the incorporation of the Law of Humanity into the different state constitutions as a completely separate part could gradually gain a decisive role in the protection of human rights in any political development. This Law of Humanity should become the minimum standard for Europe...'"

Now, I have no real context of where these speeches were given, and I now only know a very little about Viscount Templewood, but certainly, anyone arguing at such a high level (he spoke at the Royal Institute for International Affairs on Tuesday, November 20th, 1945) for the respect of the individual should be someone who is included in the dialogue about the Upstander.

It is these magical moments that I treasure in my novice research experience. I had never heard of Templewood, and had I not become a temporary member of the University Library, I might not ever have found him.

My time in Cambridge has come to an end, sadly, but I am traveling to London and cannot wait to research there.

I might even get a temporary British Library ID!!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed